By Tara S. Sims, Archivist and Special Collections Librarian.

Introduction

Books, typically seen as harbingers of knowledge and culture, can also have somewhat of a sinister side, particularly when looking closely at their anatomy and the historical period in which they were made and published. Archivists and Special Collections Librarians, Tara Sims and Kelsey Koym, at the Texas Medical Center Library (McGovern Historical Center), have recently embarked on an investigation to identify, test, and quarantine some of its most intriguing—and potentially hazardous—items: beautiful, vibrant Victorian-era books bound in materials possibly dyed with heavy metals, such as arsenic, lead, and mercury. These texts hidden within our archives and special collections not only offer a glimpse into a time when fashion and industrial practices often prioritized beauty over safety, but they also reveal a fascinating intersection of art, science, and history, underscoring the dangers faced by people in the past and the unexpected hazards that haunt the shelves of some libraries and archives today.

The Vibrant Victorian

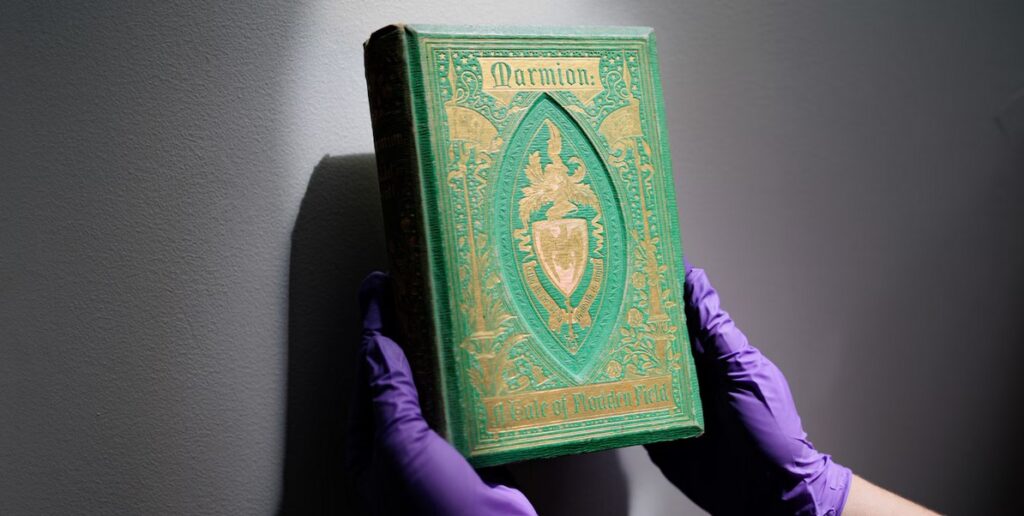

The Victorian era (approximately 1820-1914) was a period of significant social, cultural, and technological change. Grandeur, opulence, and excess were distinguishing traits of the fashion, style, and overall desired aesthetic during this period. Chemistry and engineering practices were also heavily manipulated during this time, giving rise to new and vibrant dyes created by manufacturers who used lethal substances like arsenic to achieve eye-catching, richly colored book bindings in beautiful hues of green, yellow, red, and blue. One of the most striking and popular colors of the time was Emerald Green (also known as “Paris Green” or “Scheele’s Green”). This vibrant and long-lasting green dye, far superior to other greens available at the time, became a favorite for book publishers who used it to create attractive book covers that stood out on the shelves.

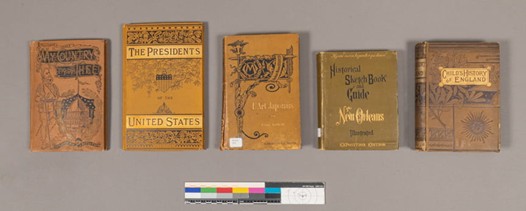

Above: These poison books each contain heavy metals used to create striking colors the 1800s. [Museums Victoria, (n.d.); Photo: Rob French]

Arsenic: The People’s Poison

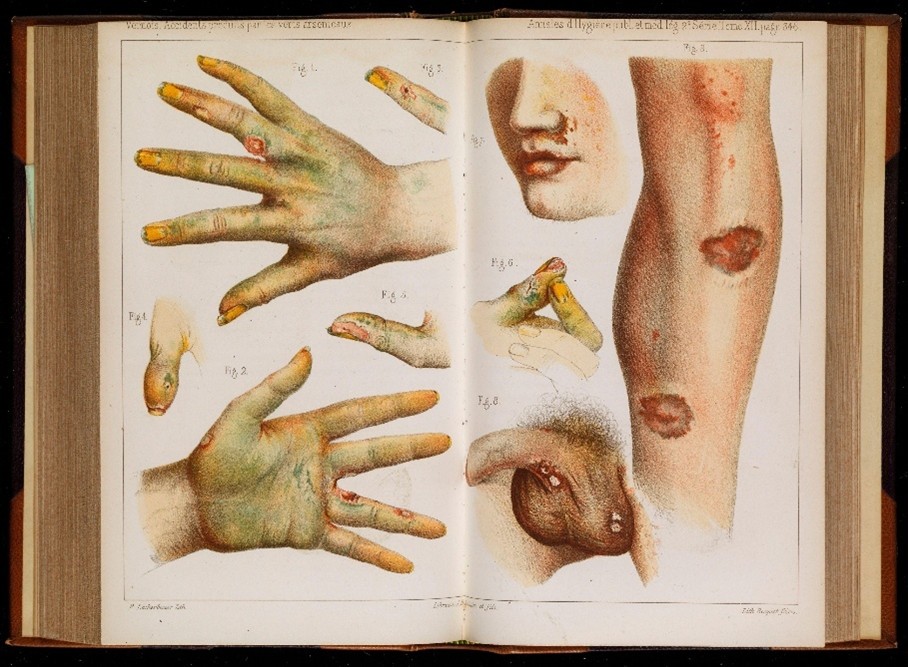

The craze for bold color didn’t stop with fancy bookbindings. It wasn’t long before these dangerous heavy metals infiltrated their way into almost every aspect of Victorian life, being present in everything from sweets and wallpaper to toys and medicines, as well as most dyes and paints utilized for decorative and aesthetic purposes in clothing and fashion accessories. As a result of this repeated over-exposure to extremely high levels of these heavy metals, Victorians of every age suffered agonizing, prolonged illnesses from things like arsenic and lead poisoning—but no one suffered more from exposure to these deadly compounds than the individuals working in the mines and factories to fabricate these products day-in and day-out. (Hawksley, L., 2016). In 1917, the Monthly Review of the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics reported that,

“Severe ulcers on the skin, severe irritation of the mucous membranes of the eyes, nose, throat, and gastrointestinal irritation […] nails drop off, and the skin appears somewhat mummified. In intense cases, death sometimes results.”

Above: Illustration from a French medical journal in 1859 showing typical damage to hands by exposure to arsenical dyes. The skin is discolored, both because of the poison in the bloodstream and the staining effect of the green dye itself. [Wellcome Collection, 1859]

Left: “The Great Lozenge-Maker”, representing the toxic adulteration of sweets using arsenic and Plaster of Paris in the 1858 Bradford sweets poisoning. [Wellcome Collection, 1858]

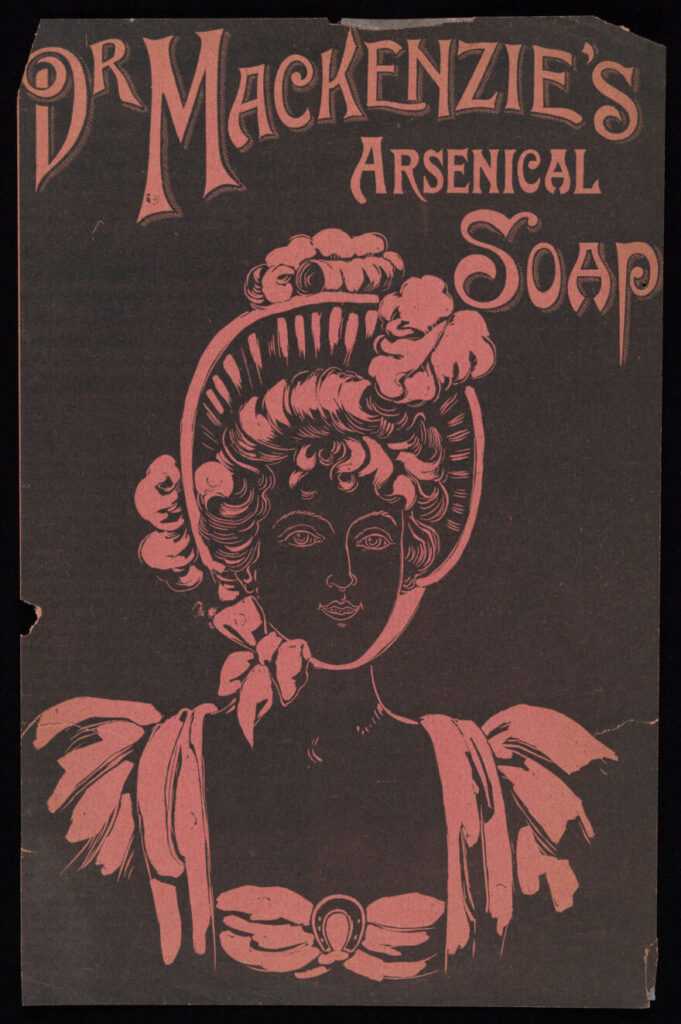

Right: Leaflet or magazine insert advertising bars of toilet soap with “a very small quantity of arsenic” to nourish the skin, whiten the hands and improve the complexion. It was “guaranteed absolutely harmless”. [Wellcome Collection, ca. 1896]

Right: Leaflet or magazine insert advertising bars of toilet soap with “a very small quantity of arsenic” to nourish the skin, whiten the hands and improve the complexion. It was “guaranteed absolutely harmless”. [Wellcome Collection, ca. 1896]

A Spectrum of Hazards

While emerald green bindings laced with arsenic are perhaps more ubiquitous and common than other heavy metals used in book production at the time, it is not the only toxic relic from the Victorian era. Many of the pigments used in the 19th century were laden with other hazardous heavy metals, such as lead and mercury. Lead, for instance, was widely used in various dyes and as a drying agent in paints and is a serious neurotoxin that poses significant health risks, particularly to children, from repeated exposure. (Museums Victoria, n.d.)

The Poison Book Project is an interdisciplinary research initiative at Winterthur Museum, Garden & Library and the University of Delaware, focusing on identifying potentially toxic pigments used in Victorian-era publisher’s bookbinding components. Recently, the initiative identified the presence of lead chromate (employed to create the pigment chrome yellow in the bindings of several 19th century books) in their collection. The appearance of chrome yellow “may range from deep, bright, or olive greens (achieved by mixing chrome yellow with various percentages of Prussian blue) to yellows, oranges, and browns.” (Poison Book Project, n.d.)

Above: Chrome yellow bookcloths in a range of hues. (Courtesy of the Poison Book Project and the Winterthur Library, Printed Book and Periodical Collection, n.d.)

Similarly, mercury was another common ingredient contained in vibrant red pigments of the time. Red mercury sulfide—which occurs naturally in the mineral cinnabar, or as the synthetic pigment vermilion—is a bright and durable pigment. For thousands of years, mercury sulfide was used to create a beautiful shade of red. (Melo, M., et al., 2010). Vermilion was widely used in the 19th century in the production of marbled end papers located directly inside the bookplates of Victorian-era books. The toxic effects on humans due to high levels and repeated exposure to mercury were well-known by the 1800s, yet it continued to be used extensively to manufacture items later found to have caused mercury poisoning, including products like the fashionable top hats worn by most men during this period. (O’Carroll, R.E. 1995).

Left: The marbled red endpapers from a book in Melbourne Museum’s Rare Book Collection was found to have high levels of mercury. (Museums Victoria, n.d.)

The Toxic Truth

As awareness of heavy metals’ toxicity grew and the loss of life increased, so did the push for safer materials in all consumer products, including books. By the early 20th century, the use of arsenic in dyes had largely fallen out of favor, replaced by safer alternatives. Nevertheless, the legacy of this toxic trend remains on the shelves of libraries and private collections around the world, a startling issue that many repositories and memory institutions are just recently beginning to realize and confront using practical mitigation strategies in an effort to eliminate any potential risks that are inherently present in situations of this nature.

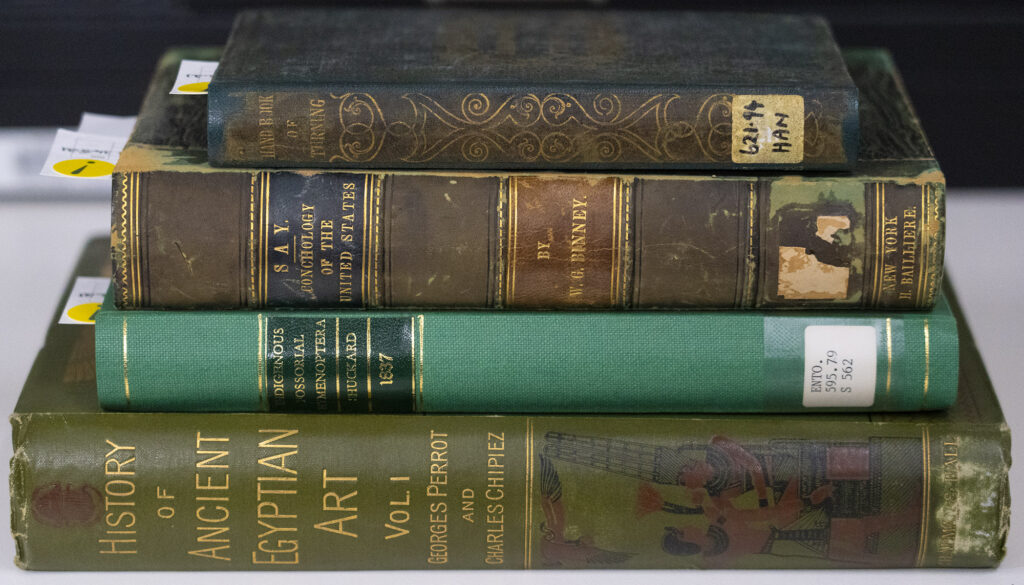

Searching Special Collections for Toxic, Victorian-Era Books at the Texas Medical Center Library

Recently, an article regarding the the removal and quarantine of four 19th century books from the National Library of France because “the covers were likely laced with arsenic” piqued the interest of several library staff members. This incident is just one of several that have made headlines in the last five or six years wherein other repositories and special collections were faced with these very same issues and responded accordingly. This article prompted the McGovern Historical Center to conduct two preliminary searches of the stacks at two locations (Texas Medical Center Library’s Rare Book Room and the MHC), and as a result of these preliminary searches (more in-depth sweeps of the stacks will be necessary and are forthcoming), we have identified roughly 10-12 books that meet at least one or two of the toxic book criteria, a helpful checklist provided online by the Poison Book Project.

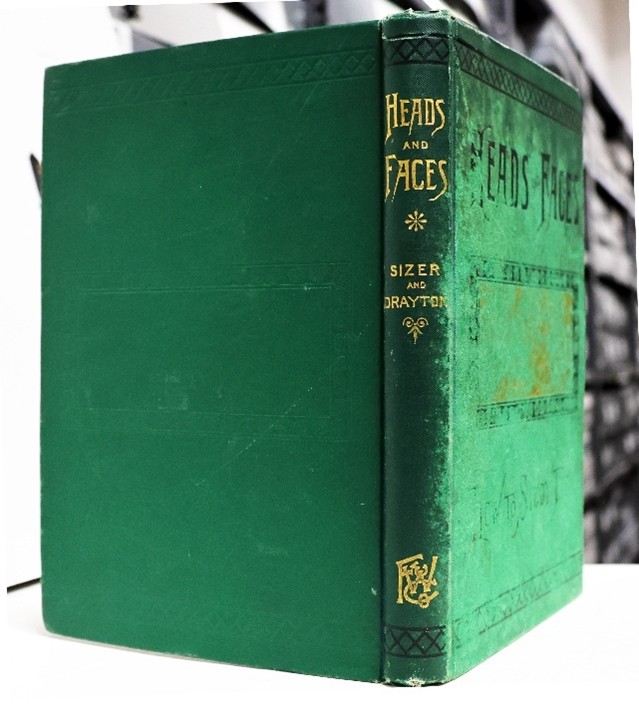

The first book found and placed in temporary quarantine during the initial sweep of the McGovern Historical Center’s stacks (pictured below), with its vivid green hues and gold leaf accents caught our eye immediately as a potential candidate that would qualify for further testing (more on testing in the next section) for the presence of any toxic compounds in its binding.This book was the first of several to be pulled from the shelves, wrapped in Tyvek, secured inside Ziplock bags, and placed in a low-traffic, temporary quarantine area designated at the McGovern Historical Center, until further investigation can be done to confirm either the presence or absence of heavy metals in its binding.

Left: RB 005. McGovern Collection on the History of Medicine 1514-2013. Heads and faces, and how to study them: a manual of phrenology and physiognomy for the people (N. Sizer, 1885).

Below: The deterioration of the green pigment and gold and black accents on the cover is an indication of the potential presence of toxic elements.

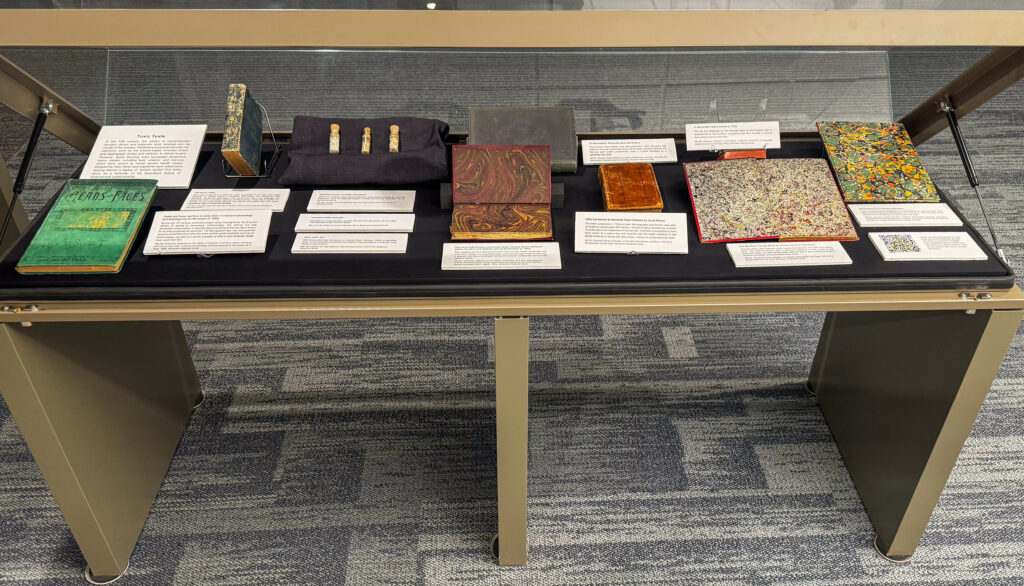

Toxic Medicine, Toxic Texts Exhibit at the Texas Medical Library

In October 2024, the McGovern Historical Center archivists curated and installed a two-part special exhibit, which is now on display at the Texas Medical Center Library. This unique exhibit offers its audience a glimpse into the not-so-distant past of the ubiquitous use of toxic medicines and toxic books that were particularly popular throughout the 19th century. Inside these exhibit cases, patrons can see and observe, up close, various medical artifacts (no replicas!) and Victorian-era books that were found in the stacks at the McGovern Historical Center and the Texas Medical Center Library’s Rare Book Room this fall.

If you haven’t seen the exhibit yet, come to the Library and check it out and let us know what you think!

Testing, Testing

The texts on display for the exhibit mentioned above, with their beautiful bindings and eye-catching marbled paper, are some of the most suspicious books (as far as being potentially poisonous) found in the library and archives thus far, and they will most likely be first-up to undergo eventual scientific testing. These tests are crucial in ascertaining either the presence or absence of heavy metals in the materials that make up a book. There are several technologies and methods of testing which are available in detecting traces of toxic components found in arsenic, mercury, and lead. The testing methods used to analyze potentially poisonous books include (but are not limited to) the following reliable techniques: (1) X-ray Fluorescence Spectroscopy (XRF); (2) Raman Spectroscopy; (3) Polarized Light Microscopy (PLM); and (4) microchemical test kits. (Poison Book Project, n.d.). While there are various testing options to choose from, conducting these tests will require specialized equipment; therefore, finding and getting access to them will be somewhat challenging. Nevertheless, we are confident that we will successfully get connected to the right individuals and tools we need to achieve this end goal. Meanwhile, if you or anyone you know has access to the testing methods and technologies mentioned above, please contact the archivists at the McGovern Historical Center (at mcgovern@library.tmc.edu) to help us get the next phase of this important project started!

The Path Forward: Safety and Preservation

Currently, the Toxic Books Project (unofficial name) at the Texas Medical Center Library and McGovern Historical Center its early stages of development and planning. Our team is strategizing and researching how to go about finding viable solutions to obtain the required testing these books need for our team to make informed, responsible decisions to protect our staff and patrons from any unnecessary exposure to potentially hazardous materials. Eventually, we might even use the data we collected to publish a small case study that offers insight into the challenges we faced, the lessons we learned, what our ultimate findings were, and how responded.

The goal of this initiative is twofold: (1) to protect our immediate community from potential exposure to known toxic properties of 19th century books; and (2) to raise awareness and provide information with others who could benefit from a case study of this nature. By sharing our findings, we hope to contribute to a broader understanding of the hidden dangers lurking in Victorian-era collections worldwide. Smaller museums, archives, and libraries, which may lack the resources for comprehensive testing, could benefit from any findings and plans of action we share to start their own poison book project.

Handling and Storage Tips for Toxic Books

Use the following tips and recommendations if you are unsure about a book’s toxicity:

- Wear nitrile gloves. Do not handle suspected arsenical green books with bare hands. Prolonged skin contact with this pigment can lead to skin lesions over time.

- Wear a mask. While this is not necessary, it is a good idea if you are handling a bookbinding with friable (flaking off) pigment, wherein tiny, harmful particles in the air have the potential to be inhaled unknowingly.

- Wash hands. Even if gloves are worn, it is essential to wash your hands thoroughly with soap and water after handling suspected arsenical books.

- Isolate books for storage. If a bookbinding component is suspected to contain arsenical green pigment, place the book in a Ziplock or polyethylene bag to minimize handling and to contain any potentially friable pigment. The sealed book can be stored as-is or placed inside another box for additional protection. If humidity in the storage area is a concern, consider adding a small silica gel packet to the bag to help manage moisture levels.

- If possible, remove books from circulating collections. Transferring arsenical books from circulating collections to the rare book collections (or quarantine, for that matter), ensures they are not checked out or used in patrons’ homes.

- Wipe down surfaces. When handling books bound with potential arsenical green pigment, use hard surfaces like tables and avoid upholstered surfaces such as armchairs. After handling, clean any hard surfaces that encountered the book using a damp, disposable cloth. (Poison Book Project, n.d.)

A Final Thought

While the idea of toxic books on anyone’s shelves can be scary and alarming, it’s just as important to note that the risks described in this article are generally very low in cases of casual contact with books from the Victorian period. The substances are typically bound within the materials and do not pose a significant threat unless the books are damaged or exposed to moisture. In comparison to the constant exposure and ingestion of these harmful substances the Victorians endured over prolonged periods of time, the chances of 21st century librarians, archivists, and patrons being ravaged by arsenic poisoning are extremely low. Nevertheless, at the Texas Medical Center Library, we’re taking proactive measures to plan for the eventual assessment of our collections for the presence of these toxic substances. By carefully examining, identifying, testing, and quarantining these books, we aim to mitigate any potential risks to staff and patrons. As we continue our investigation, the Texas Medical Center Library is committed to preserving these historical artifacts while ensuring the safety of our staff and visitors. Handling procedures are being updated, including the use of protective gloves and other safety measures when dealing with these potentially hazardous books. With that said, as we continue to delve deeper into our collection and this project, we’ll keep our community informed about our findings and the steps we’re taking to address any risks. Your safety, alongside the preservation of our cultural treasures, remains our top priority.

Stay tuned as we attempt to uncover more secrets of the past—safely and responsibly!