By Alethea Drexler

Archives assistant

Next year is the centennial of the Texas Medical Center Library. The Library started out as the library for the Harris County Medical Society, which was founded in 1903[1], so it predates the Medical Center by several decades. In celebration, The Black Bag is going to include a series of short posts featuring excerpts from the South Texas Medical Record/Medical Bulletin of the Harris County Medical Society (same publication, different names; kind of like Montrose/Studemont/Studewood Street) from the 1910’s.

The Medical Record/Bulletin published papers by Medical Society members, Medical Society business, information on professional organizations, and “personals”, which were short accounts of events in members’ lives. The personals were chatty and, as occasion permitted, often humorous. There was also advertising, although I think some of the full-page ads were removed when the journals were bound, probably to save space and because they were repetitive among volumes. The ads that remain are interesting in their own rights, and those that don’t appear here will surely be used in later posts.

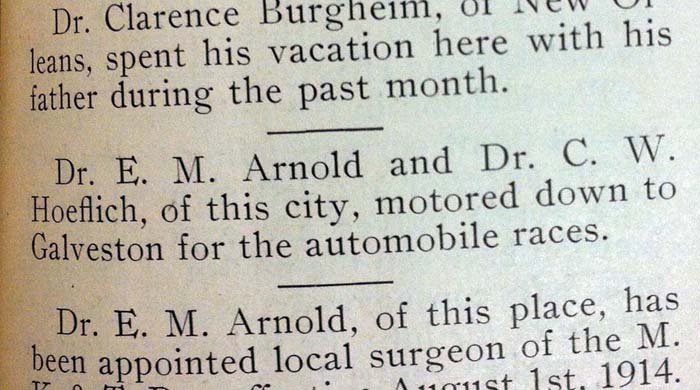

We’ll start off with what the Harris County Medical Society had to say about cars (V.6, N5, April 1914, page 17):

As one reads through car-related jibes in the personals, and car-related advertising, two things come to mind:

1) There is definitely a hierarchy of “cool” versus “uncool” cars.

2) Doctors have always liked the cool cars. Even if it means appreciating them vicariously (V.7, N.3, August 1915, page 27):

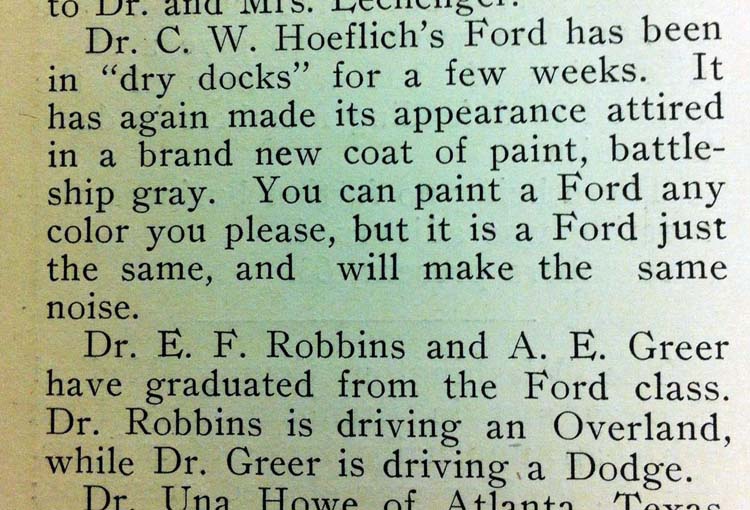

Fords are uncool. Fords were starter cars, unrefined cars, plebian cars to be mocked by drivers of cool cars and replaced as soon as finances permitted, in this case, the Bulletin suggests, by an Overland[2] or a Dodge[3] (V.10 No.1, May 1916, page 24):

Fords are uncool. Fords were starter cars, unrefined cars, plebian cars to be mocked by drivers of cool cars and replaced as soon as finances permitted, in this case, the Bulletin suggests, by an Overland[2] or a Dodge[3] (V.10 No.1, May 1916, page 24):

The first Dodge cars came into production in November, 1914[4] (Dodge had been a parts manufacturer, supplying pieces to earlier auto companies, since the turn of the century), so Dr. Greer was cutting edge in his choice of cars.

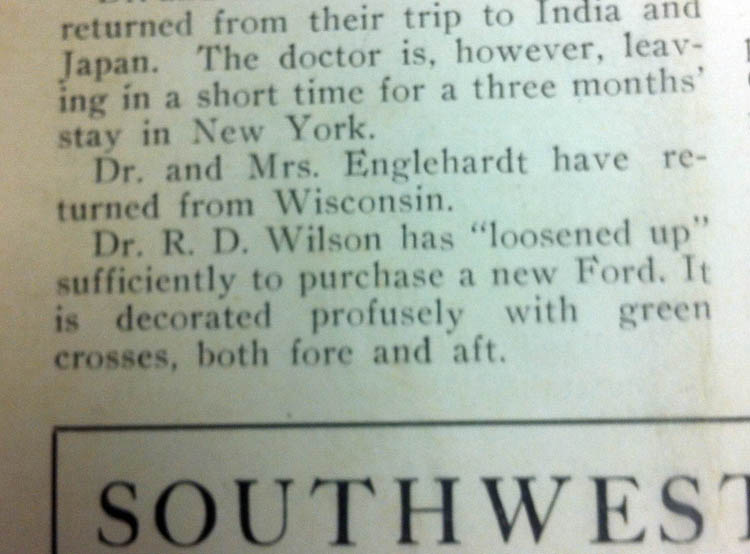

Dr. R.D. Wilson, who sounds as though he must have been a bit of an eccentric, got ribbed about his new Ford in September, 1915 (V.9, N.6, page 26):

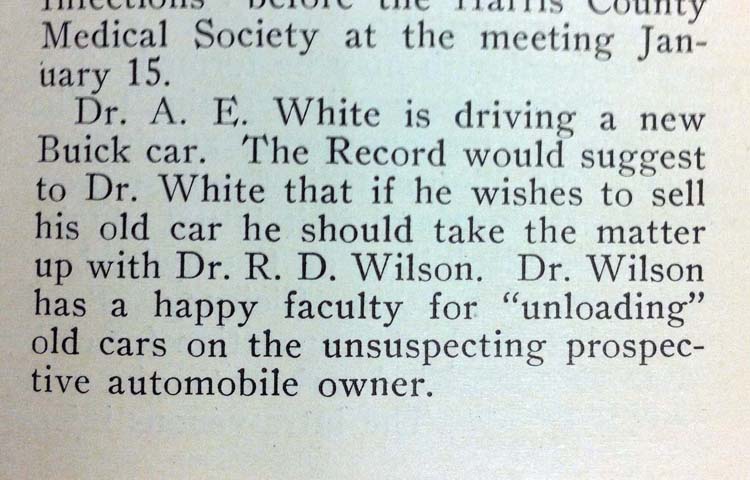

He must also have been, um, thrifty. Possibly to a fault (BHCMS, V.9, N.9, January 1916, page 23):

Buicks seem to have been popular. The column above also mentioned that “Santa Claus” brought a Dr. Cruse a new Buick. Dr. Jesse Burditt even ordered a new Buick in May, 1915 (V.9, N.5, page 23), and had to wait extra time to get his special-ordered red wheels. If his car was a coupe, it would have looked like the one seen here[5] (the personals don’t mention the body color, though in 1915 it was probably black). Alas, Dr. Burditt didn’t get to enjoy his new car very long; Volume 9, No. 11 (pages 16 and 21), in March 1916 published notice of his sudden death at age 45, from heart failure.

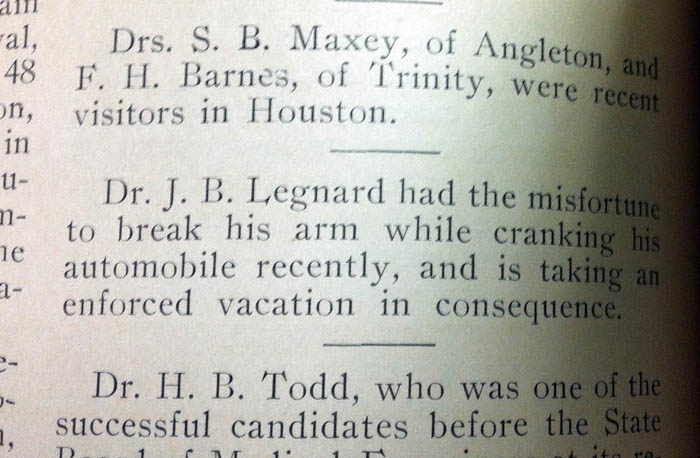

Driving in Houston in the early years of the automobile had its own set of hazards. Sure, traffic was probably slower and less congested, but we can all be thankful we have starter motors[6] and no longer have to crank-start our cars (V.8, N.4, February 1915, page 24):

Here is a YouTube video on how to safely crank-start a Model T. Safely, so it doesn’t shatter your arm. My Mazda has a push-button ignition; I don’t even have to fumble for keys on dark winter mornings. We’ve come a long way, baby. (Here’s another YouTube of a 1914 Model T touring car in action.)

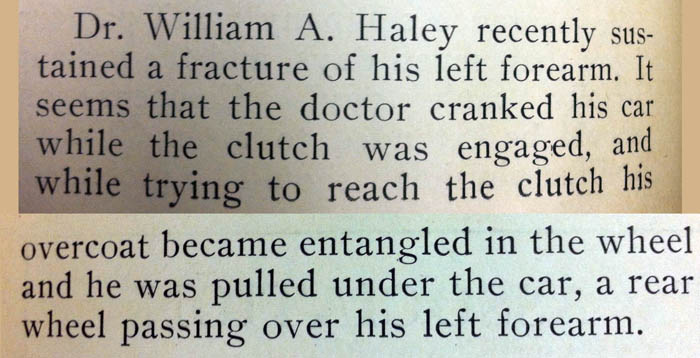

Of course, even if the car didn’t get you with the crank, you couldn’t be sure it wouldn’t sneak up on you later (V.8 N.5, February 1915, pages 26-27). It was possible to run yourself over even in the days before automatic transmissions:

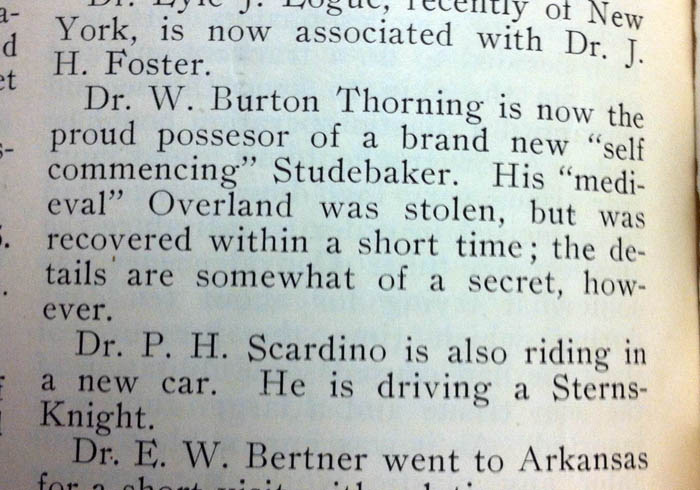

This is why it was such a big deal in December, 1915 (V.9 N.8, page 22) when Dr. W. Burton Thorning replaced his stolen Overland with a “self-commencing” Studebaker.

Dun’s Review magazine published an account of and exhibit in Madison Square Gardens, New York, and the Paris Automobile Salon[8] in September, 1912, that made note of the stir caused by new self-starting Overland and Studebaker cars.

It’s of interest that the other car mentioned in the clipping above is a Stearns-Knight. Stearns-Knight was a luxury car brand produced in the first quarter of the century[10]. It and Overland were both eventually purchased by Willys[11], which survives today as Jeep.

Most of the cars mentioned in the journals belonged to brands that no longer exist; many of them for many decades. Cadillac (V.3 N.6 October 1912, page 5), Dodge, Buick, and Ford have survived.

Studebaker closed down in 1966[12] (V.6 N.5 April 1914, page 17);

Willys-Overland (as a brand name) disappeared in 1963[13] and Hudson in 1957[14] (V.6 N.5 April 1914, page 22):

The rest were gone long before that:

1) Chalmers[15]: Dr. Roy Wilson’s new Chalmers was “incinerated” (unfortunately, no details are provided) in April 1913 (V.4 N.6, page 25). Chalmers was absorbed by Chrysler.

2) Oakland[18], a mid-range General Motors brand that fell between Chevrolet and Buick in the prestige hierarchy (V.3 N.2, June 1912, page 5).

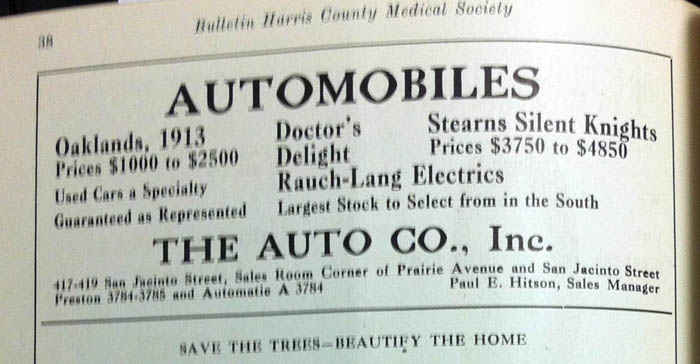

3) This ad from October 1913 (V.3 No.6, page 38) features Oaklands, Stearns-Knights, and Rauch and Lang[21] electric cars. Note the considerable price difference between an Oakland and a Stearns-Knight. Electric cars were more common early in the century than you might think. More pictures of Rauch and Langs, and other early electric cars, can be seen here[22].

4) G.W. Hawkins, Co. (V.3 N.1, May 1912, page 6), sold four brands, none of which survived the 1920’s: Stoddard-Dayton[23], a high-end car that would be purchased by Maxwell the following year; its lower-end subsidiary Courier[24]; Maxwell[25], which, in turn, was absorbed by Chrysler; and Columbia[26], and extremely early brand that produced both gasoline and electric models (these would have been available only secondhand in 1912, or perhaps Hawkins also serviced them).

5) Cartercar[28] (V.6 N.5 April 1914, page 18), which gets the award for the best lettering, had been purchased by General Motors in 1909 and would be discontinued the next year. On a side note: Cartercar founder Byron Carter died in 1908 of gangrene that stemmed from a jaw wound acquired when–drum roll, please–he was crank-starting a car and the crank kicked and hit him in the face[29]. Carter was a friend of Cadillac founder Henry Leland[30], who developed the electric self-starter that would eliminate the dangers of crank-starting.

The “gearless” Cartercar had a friction-drive transmission[31]. Friction-drive transmissions seem mostly to be used in things like go-karts and record players, which suggests that they weren’t very efficient in big, heavy, cars; the idea was used in a few very early brands but then disappeared. It has (sort of) reemerged more recently as the continuously variable transmission[32], which is belt-driven but also does not have set gear ratios. If you scroll through the pictures underneath this 1909 Cartercar[33], you’ll see a picture of the transmission wheel (image 66).

Sources consulted:

1] Harris County Medical Society history.

2] Wikipedia: Overland Automobile

3] Wikipedia: Dodge

4] Meadow Brook Hall: Dodge Brothers

5] Prewar Buick.com

6] Wikipedia: Starter (engine)

7] Hand cranking – safe and easy, from abarnyard.com

8] Dun’s Review, V.20 N.1 September 1912, pages 80-85. Found on Google Books.

9] Studebaker National Museum

10] Wikipedia: Stearns-Knight

11] Wikipedia: Willys

12] Studebaker National Museum: History

13] Kaiser-Willys Auto Supply, LLC: History

14] Wikipedia: Hudson Motor Car Company

15] Wikipedia: Chalmers Automobile

16] Chalmers Automobile Registry

17] Allpar.com: History

18] Wikipedia: Oakland (automobile)

19] GM Heritage Center

20] Oakland Owners Club International

21] Wikipedia: Rauch and Lang

22] Chuck’s Toyland

23] Wikipedia: Stoddard-Dayton

24] Wikipedia: Courier Car Company

25] Wikipedia: Maxwell automobile

26] Wikipedia: Columbia automobile company

27] Hostetler’s Hudson Museum, Shipshewana, Indiana

28] Cartercar.org

29] Wikipedia: Cartercar

30] Wikipedia: Henry M. Leland

31] Wikipedia: Friction drive

32] Wikipedia: Continuously variable transmission

33] Vintage Cars USA.com

34] Examiner.com: “Cartercar: Tracing the origins of the CVT transmission” (July 23, 2009)

35] Motor, V.22 N.6, September 1915, page 94 (Willys-Overland advertisement for electric self-starters)

36] Motor, V.22 N.6, September 1915, page 95 (Cartercar advertisement)